Though much is taken, much abides; and though

Tennyson, Ulysses

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are,

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Looking for Jesus

Somewhere inside the gospels is the wisp of the Jesus who breathed, ate and drank, defecated, and, quite possibly, copulated. A charismatic, magnetic individual who like most leaders no doubt harboured psychopathic tendencies. Yet there is no more poignant moment in all the scriptures than the Last Supper and Garden of Gethsemane.

A man convinced he was the son of God, betrayed by one of his best friends, no longer trusting anyone, crying out to his father to save him. (Let’s overlook how the lads meant to be keeping watch, Peter, John, James, were – to the Lord’s chagrin – sleeping through all this, and so who was it who could have known the words he was praying?) Jesus knew that he was about to lose everything and suffer unimaginable pain and humiliation in full public view. So all he asked of this disciples was to be remembered, somewhat contradicting his previous bold and outrageous claims of divinity and ability to rise from the dead. He begged that even in the most mundane of activities, those of breaking bread and drinking wine, his friends would remember him, as time does it work and memories fade, the still-living having to get on with their lives and move on. That was all the comfort he asked for, to be remembered.

Each of the gospel writers had an agenda. What we read now is the result of a layering on of the ideological and political colour which was expedient for the early Christian communities in a fraught period of Roman rule over Palestine and the Jewish people.

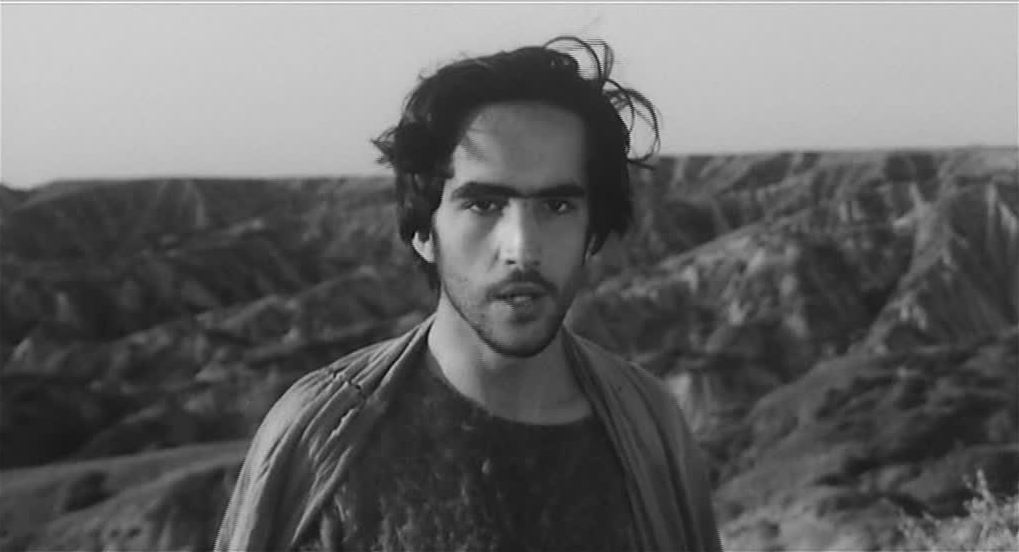

Il vangelo secondo Pasolini

Strip away the agendas and what is left? In one attempt to do so, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film of Matthews’s Gospel, each actor is invested with profound humanity, even the bad guys, like Herod the Great, reputed massacrer of the innocents, the uppity chief priests and Judas Iscariot. Unfolding events are reflected on the close-ups of their faces, you see their minds process the happenings in real time, produce a smile or grimace. We see John the Baptist spitting out his lines as he gazes disdainfully on the priests in their fancy attire passing by aloof and proud.

Razza di vipere! Chi vi ha suggerito di sottrarvi all’ira imminente?

My successor will sort you out, he promises, just you wait and you will get your comeuppance.

Egli ha in mano il ventilabro, pulirà la sua aia e raccoglierà il suo grano nel granaio, ma brucerà la pula con un fuoco inestinguibile!

Jesus becomes like him, the curses in Jerusalem – guai a voi, scribi e farisei ipocriti! – that mirror the earlier Beatitudes elevating the poor and unfortunate, are pure unrestrained spleen. And also ill-advised: by now it is a matter of time before they eliminate him.

Pasolini whose oeuvre is otherwise rife with grim scenarios and revolting violence, spares the viewer, and there are no gratuitous images of the physical cruelty meted out to Jesus. He has his crown of thorns but there is no brutal beating up; one of the other crucified is seen howling in pain as the nails are driven in, but Jesus is immediately shown on the cross, uttering his last words. Pasolini does not pad out the gaps of the narrative with sentiment or folderol. It speaks for itself, though the film is clearly an interpretation laced with stark political intent.

Punch upwards only

With a distinctly 1930s vibe in the state of the human race today, those on the left, especially white non-Jews of European heritage, do well to take some perspective on the degree of violence and injustice which is being perpetrated by men in positions of power around the world in Xinjiang, Myanmar, Sudan and Russian-occupied Ukraine, and of course Gaza. They seem to get unusually triggered by the actions of the state of Israel, and I recall what Hannah Arendt wrote in her book about the trial of Eichmann, that Israel had displaced onto innocent Palestinians the punishment that rightly belonged to the Europeans who for centuries persecuted and abused their Jewish neighbours, a trend that culminated in the Shoah. The colonising West attempted to absolve its collective guilt by allocating a ‘homeland’ to the Jewish people and making the largely Muslim populations of the Middle East pay the price. The cycle of dehumanisation continued unabated.

The gospels were composed in the wake of the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus in 70 CE, when the first Christians calculated they would be better off pivoting away from their native Jewish community with its insurrectionist elements. Tension builds along the narrative arc of each gospel, as Jesus prods and excoriates the hypocrisy of the men in power to the point where he overreaches and becomes such a security threat that he is executed. He only ever punches upwards. Yet the gospel writers would have it that Jesus had barely a bad word to say about the depraved excesses of the far more powerful Imperial overlords of the time, the ones who eventually were the only ones able to decide Jesus was too troublesome and should therefore be tortured publicly to death. In spite of this, Jesus flipped accepted logic on its head: the first shall be last and the last first. This he relentlessly rammed against the powerful religious authorities, who would rather take a rest on the Sabbath than relieve people of their hunger and suffering, who would hold to strict dietary laws when in fact it is not what goes into your body – whether words, observations or food – that makes you unclean; it is the shit that comes out – the purging of all meats, as the King James Version put it – that makes you unclean.

This is a radical theology of goodness towards the world. It suggests every word and action you perform, or indeed do not perform, creates a field of impact around you. I heard a sermon by the then Rector of Hackney to this effect; when you do small things you shouldn’t do, however small, he said, you are adding to the brokenness of this world. It not only informs individual responsibility; it points to the need for a humane politics of justice for the weak and retribution for the destroyers of life and freedom, whether they are Putin, Xi or Netanyahu.

Buona Pasqua.

Leave a comment